Storytelling with Design: MANTA’s Betsy Goodrich on Her Creative Process

According to MANTA co-founder and VP of Design Betsy Goodrich, "When clients come to MANTA, there is always a story - of a need, a problem, or a realization - that needs to be uncovered and told."

Storytelling is one of humanity's oldest forms of communication. A great story sparks the brain’s reward system, with an emotional charge, solidifying the story in our memories. Just like stories told only in words, visuals can communicate narratives and evoke emotions. Likewise, the products we choose to include in our lives elicit positive feelings and tell stories of who we are, who we aspire to be, and what we value to the world around us.

For Betsy and MANTA designers, the process of creating new products is all about telling stories with design. To drive this idea home, Betsy often asks robotics clients, "Is your product or brand more Wall-E or EVE?" While both characters from the Pixar movie are robots with similar basic functions, their designs immediately convey the characteristics that make them distinct.

Wall-E is designed almost exclusively around his function as a robotic trash compactor. His all-terrain treads, shovel hands, and rugged exterior are built for this demanding job while reflecting the wasteland environment around him. Meanwhile, EVE's sleek enclosure and anti-gravity movement reflect her futuristic, otherwordly origin on a spaceship. Each robot's design wordlessly tells the viewer a story of where the robot is from and what it can do.

Similarly, Betsy's aim with product design is to convey the story of a product and who it's meant for in a single glance. In this interview, she reveals how she uses industrial design to build products that tell compelling stories to MANTA clients and their customers.

"Our role as designers is to make what is possible real."

Q: How do you understand the story you need to tell when designing a new product?

Betsy Goodrich: Our design process starts by digging into a lot of details and focusing on users, their environment, and their expectations. Those expectations are also influenced by current design trends and what the product might sit next to - on a lab bench, on an office desk, or in someone’s home.

My team and I usually ask: would this design lead the trend or follow the trend of what customers use or work with now? How would this design compare to alternative products that someone might consider buying?

We also like to bring out reference products to help clients identify the story they want their product to convey. Often a client will gravitate towards a particular aesthetic, but can’t figure out why. My job is to translate the visual elements of a reference into the words and story a client wants to tell.

With those expectations in mind, we can craft a story with a design that will speak to clients and their customers.

When working with a client on developing a new home smart speaker, MANTA designers started by understanding the evolution of forms and materials used in existing speakers on the market.

Q2: How do you go about storytelling through design?

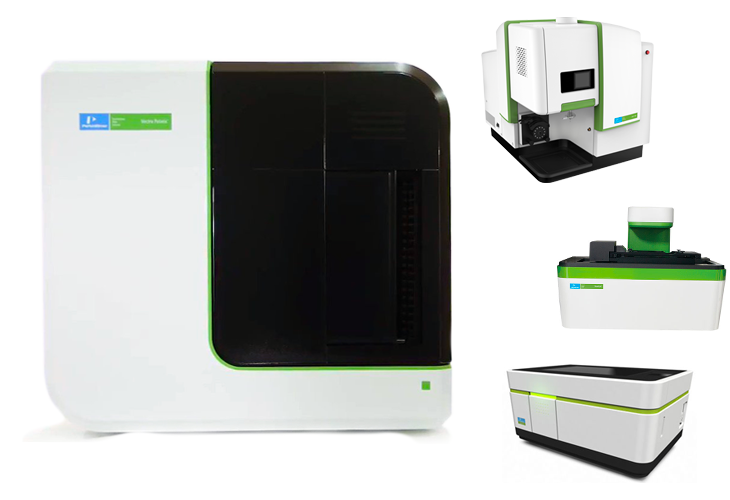

Betsy Goodrich: I draw heavily on my training and experience to communicate the intended story through lines, color, and form. For instance, when developing PerkinElmer's Vectra Polaris (now an Akoya Biosciences product), we wanted to highlight continuity in a product line. Our team adopted the form that other instruments in the line had: crisp edges in one plane contrasted with rounded corners in another.

Design is not only about the aesthetics of a product, but also about interaction - how intuitive, approachable, and usable that product is. For example, color can highlight interaction points while recessed forms with a neutral finish allow other elements to fall away.

Often there’s also a technological story to feature. On a recent product, I wanted to emphasize the new, cutting-edge camera and minimize other aspects. So I had to think creatively about using form, color, materials, and illumination to draw attention to that aspect.

By studying other Perkin Elmer products, MANTA's design team was able to design the Vectra Polaris as an innovative product that still aligned with the brand's design language.

"A good designer is always looking to find an idea that will inspire people, and then working to bring that vision into the world."

Q: How do you decide what design concepts actually tell that story?

Betsy Goodrich: As soon as we meet with a client, I will immediately start sketching ideas and finding descriptive words. Once we speak with them more, our designers and engineers will generate a set of minimum product requirements, which starts to guide the concepts we sketch and our design decisions.

I like to break out those requirements into functional versus inspirational goals. This is where it becomes important to really understand the company’s unique position and opportunity. Is a company only looking to refresh a product to make it feel new, or are they interested in being really disruptive?

Sometimes, a company has had a very successful product line, and they want that to effortlessly translate to a new set of products. Although they’ve had a successful story, they need to evolve that story and design as time goes on. That can be a challenge for a lot of teams because they’re so attached to what something currently is that they can’t envision what it could be.

That’s where the inspirational goals come in. Our role as designers is to make what is possible real. If I sense that a client wants to evolve, we present concepts that push them further and give them a new vision of what a product could be.

Colorized concept sketches bring the story of the product to life to communicate ideas that haven't been manufactured yet.

Q: What changes in your design's storytelling as you go from a sketch to a physical model or prototype?

Betsy Goodrich: When you create in two dimensions, you make assumptions about the product form and how it might function. Even when you have a CAD model, you might not fully appreciate how it occupies space in the real world until you make a physical model. Once something is physical and put to use in the intended environment, you will identify new challenges and opportunities that impact the user experience and the story you want to communicate.

With the physical model, you can test some of your assumptions and act out your product’s story. You can observe people’s first impressions, what draws their eye, and where they naturally reach to touch something. You may find that the configuration is confusing, or if it's a wearable product, that it's uncomfortable for some users. That’s why it’s critical even with really rough prototypes to test them, ideally early and repeatedly with your target users.

Experienced product designers have a good sense of what assumptions to look out for before something moves to the 3D model. As a designer that often means you will be concerned about aspects of a design that’s not yet on anyone else’s radar. Generating full-scale 3D models allows the entire team to explore use cases early and iterate real-time in order to deliver the best stories with your product.

Building a looks-like prototype of the Lexagene LX2 analyzer aided our understanding of its usability and helped generate buy-in for the product.

"Design is not only about the aesthetics of a product, but also about how interaction - how intuitive, approachable, and usable that product is."

Q: How else do you work with others and within the constraints of a project to bring a product's story to life?

Betsy Goodrich: In addition to thinking about budget and timeline, I try to get a sense of the team and understand their expertise and their gaps. My goal is to build a rapport to understand not just what the project team is doing, but also the narrative of where the entire company is headed.

Often, we advise teams about designing for production to bring a product to market. We never want to hand a client designs that they can’t actually implement. That just leads to frustration that the final product doesn’t look anything like the proposed sketches or renderings, and doesn't communicate what was intended. It’s the difference between a one-off concept car versus something that is successfully produced in volume.

With an established company, I also study their products to understand their materials and production capabilities. That way our designers can recommend a production process that aligns with their capabilities and makes sense for the particular product, whether for high or low-volume production.

Ultimately there’s a careful balance of building something so it can be used and serviced well, manufactured at the appropriate quality and cost, and still project the intended story. A good designer is always looking to find an idea that will inspire people, and then working to bring that vision into the world.

In redesigning the Neurometrix Quell wearable device, MANTA designers considered usability, system architecture, and production needs throughout the product development cycle.

Ready to Design Your Product?

Whether your team needs to envision a new product concept or redesign an existing one, MANTA's product design team can help. Start now.